In recent months, Reddit’s algorithm seems to have taken a hard turn. I’m seeing a lot more of the kind of engagement-bait content that traditionally pops up on Facebook and Twitter/X, and fewer of the subreddits I’m actually subscribed to.

One of the subs that keeps popping up — which kind of straddles both sides of the gap — is OKBuddySnyderCult. It’s what’s called a “Circlejerk” Subreddit, succinctly described by Redditor apopheniac1989 as “a self-congratulatory echo chamber where people surround themselves with people who agree with them.” In this case, it’s all about making fun of hardcore Zack Snyder/DC Extended Universe superfans.

The “OKBuddy…” Subreddit has crossed my feed a few times recently, presumably because I keep clicking on them to see what they say. I’m disinclined to engage with the sub, because frankly it feels mean-spirited to have a community dedicated to dunking on others, even if those others might “deserve” it.

This morning, though, I saw a post that I actually had some thoughts on. The premise was this:

“I can understand the appeal of joining a cult. Community, organizing goals, a religious-like belief system. But why a cult about mediocre films like [Man of Steel and Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice]?”

Now, let me give any new readers a quick, bird’s eye version of my relationship to Man of Steel, Batman v Superman, and Zack Snyder’s Justice League, all of which I covered extensively at the time of their releases:

I actually very much enjoyed Man of Steel, in spite of being critical of some of its flaws (particularly in the depiction of Jonathan Kent). I thought Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice was structurally a mess, but held together by some really compelling stuff. I could see even in the theatrical cut where some of the holes were that eventually got patched in the movie’s “ultimate cut,” and intuitively understood some of the things that I admit were confusing to most viewers. These aren’t my favorite movies, but I thought they were enjoyable enough.

I was forgiving enough of the Snyder/Whedon Justice League, until I saw Zack Snyder’s Justice League — the long-clamored-for “Snyder Cut” — which I did think was much better, even if it was frankly absurd that a four-hour assembly cut of a failed movie would get a wide commercial release.

After having heard a lot of stories through the grapevine over the years, I decided that it might be interesting to try and get to the bottom of the whole “Snyder Cut” thing. A few months before Zack Snyder’s Justice League was announced, I put together a pitch document asking my employer for permission to write a book about the making of the movie and its many, many stumbling blocks.

(I was exclusive to ComicBook at the time, and not allowed to work on a book that they considered a potential conflict of interest, so I had to pitch everything to them first.)

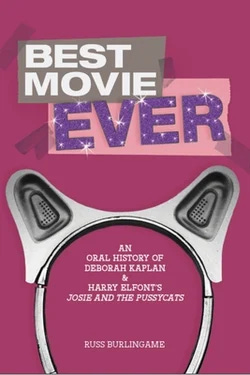

I never heard back from ComicBook or its parent company, CBS Interactive, about the Snyder Cut project. Eventually I decided instead to write a book about the making of Josie and the Pussycats, which worked out much better. I can’t imagine the misery of being permanently associated with Snyder’s DC movies and having that association taint my existence on social media, where both sides are frankly kind of insufferable.

So, with that loooong prelude out of the way, let me see about answering the “cult” question to the best of my ability.

Are Snyder’s fans a cult?

I mean…yes and no. I do think the loudest, most irrational voices online represent a small percentage of Snyder’s overall fan base. Certainly, though, those people have built up a cult of personality around the filmmaker. It’s why people who originally wanted to see a Ben Affleck Batman movie are now buying toys and merch for Snyder’s not-quite-a-Star-War franchise, Rebel Moon.

I think there is some question as to how actively Snyder cultivates that, as opposed to simply tolerating it. I think the answer lies somewhere in the middle. I’m not convinced he cultivates it and he certainly doesn’t try to weed it out. I think (to continue with this unintentional farming metaphor) that he mostly just collects the naturally-occurring crops and uses them to his benefit.

Snyder seems, by all accounts, to be a good guy to work with; he seems to remain friends and carry some influence with basically all of the actors from his projects, many of which return again and again as part of his ensemble. I have a difficult time imagining that he is actively trying to egg on the worst people in his fan base. Maybe that’s naive.

For the sake of argument, though, I’m going to accept the “cult” claim at face value, because I feel like the actual question being asked is worth interrogating: Why Zack Snyder? Why these fucking movies?

What’s That Thing That’s Like An Asshole?

First and foremost, people are allowed to have their own opinions. There are probably some people who are overstating their love for these movies, or who like them performatively, or…whatever. But by and large, I think critics of Snyder’s DC movies often take for granted that the movies are terrible, and nobody could actually, sincerely enjoy them.

That’s both demonstrably false and deeply silly.

These movies are very flawed, but there are many much, much worse movies out there, many of which have ardent defenders. You have to start from the position that some people just…enjoy the fucking movies. Otherwise you’re already not going to able to get from point A to B. If you assume nobody can earnestly enjoy the thing, then it becomes harder to explain everything else I’m going to talk about.

Much of Online Fandom is About Finding Identity and Community

Fandom in general, and in particularly online fandom, is often about outsiders who are finding their “in-group” through sharing with strangers who have mutual interests.

That’s, like…the whole point of finding a group.

People can derive a lot of (one might argue an unhealthy amount of) their identity and self-esteem from the groups they’re part of. In many cases, those groups also become a core part of fans’ social lives, and that allows the larger group to shape aspects of the indivdual’s personality. So a fandom that’s permeated by negativity, toxic behavior, etc., will reflect back on the individual and potentially encourage that kind of behavior in them.

Also Online Fandom Sucks.

Online fandom as a whole has a tendency to get pretty toxic. The Superman fandom has found ways to be at one another’s throats for years — and he’s fucking Superman. Somehow, I’m sure there are unexplored pockets of a Mr. Rogers subreddit where fans are calling each other F-slurs. That’s just how the internet works.

That’s not to make excuses for the loudest and worst of Snyder’s fans, but it’s something that we have to accept in the same way we have to accept that, whether or not you agree with them, some people just like the fucking movies. What you see in the “Snyder Cult” is not unique to Snyder’s fans; they just stumbled into a set of conditions that no one could reasonably have anticipated.

Snyder’s Films Depict A Very Specific Kind of Hero, And It Appeals to People

Nerds of a certain age remember being relentlessly bullied for reading comic books. I certainly was, in middle school at least.

While it took about a decade or so to fully reverberate through the larger culture, the stigma around comics as junk reading for losers really started to fall away in the mid-to-late-1980s, when comics like The Dark Knight Returns and Watchmen broke through to the mainstream.

The narrative, pushed heavily by critics and even some teachers, was that it was “okay” to like comics if they were sufficiently “mature.”

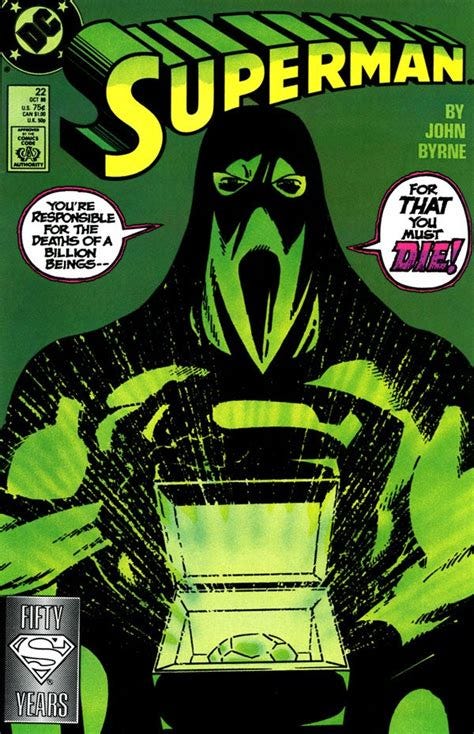

That push, combined with the cynicism and irony that defined much of popular culture in the late ‘80s and throughout the 1990s, reshaped what many readers considered an “acceptable” heroic archetype. It’s part of why we got the ultraviolent, grim-and-gritty comics of the ‘90s, and it’s part of why John Byrne’s Superman struggled to be comfortable with his role in the world. It’s a huge part of why, in his final story before leaving the titles, Byrne depicted Superman as an executioner who put a trio of villains to death by Kryptonite poisoning.

“We didn’t invent that,” writer David S. Goyer told me at a Comic Con party. I had asked him about the decision to kill General Zod at the end of Man of Steel, and he cited Byrne, arguing that it wasn’t fair to criticize him for doing something the comics had already done.

He wasn’t the only one who felt that way.

“It was hugely controversial and I think if the Internet had existed at that time, it would have been that times three,” legendary Superman writer/artist Dan Jurgens told Comicosity. “I always thought that if Superman was going to be put in that position, that it had to be a more immediate threat. It didn’t bother me so much, Superman killing the Kryptonians, as it was him being just a stone-cold executioner. If you think of that cover — there’s a green cover and I think it was Superman itself where he’s actually wearing the hood like an executioner would wear. That was, to me, the problem. If you wanted to have Superman kill the Kryptonians, I think it had to be a situation where innocent life was in immediate peril and the only way to stop them from taking innocent life was to kill them. At that point, Superman makes the same decision, but he’s much more Superman as part of that. And the funny thing is, everybody gets twisted in knots over of that scene in the movie — yet that’s what Superman did. When Superman kills Zod in the movie, it’s because there are human beings there who are in immediate danger.”

There are those who would argue that Superman should never kill — that there is always another way. One of those is Mark Waid, who co-created Alex Ross’s Kingdom Come and who was a vocal critic of Man of Steel. But to many, especially those who grew up either without comics, or with post-John Byrne comics, that seems like an overly-idealistic approach to extinction-level threats.

Zack Snyder’s reputation was built on 300, which adapted a graphic novel by Frank Miller. Like virtually all of Miller’s work, it was built on violence, rugged individualism and black-and-white morality. There is an inherent cultural conservatism to Miller’s heroes, who were already the embodiment of toxic masculinity years before that phrase really entered the cultural lexicon.

I don’t believe Snyder’s fans are inherently right-wing, but I do think that there’s a Venn diagram looking at people who follow Snyder and Andrew Tate on social media, and it’s likely got more overlap than I would be comfortable with.

Snyder himself makes films that are more akin to Jerry Bruckheimer than Michael Bay. While Bay makes unapologetically masculine movies that rarely feature any fleshed-out women characters, Snyder’s projects like 300, Sucker Punch and Rebel Moon put women front-and-center as often as not. Granted, they’re all dressed very sexy…but so are most of the men in those movies. Zack Snyder is just a director who seemingly loves the human form.

Nevertheless, if you ignore the actual genders of the protagonists, the “vibe” of Snyder’s films are incredibly masculine. They also — both in form and content — feel like those “mature” comics that made it okay to be a fan in the ‘80s. Snyder’s not making a lame movie about Superman; he’s making a badass movie where the word “Superman” doesn’t even appear until the last two minutes! And yeah, Jena Malone will totally kill your ass in Sucker Punch, but she’ll also dress in such a way that makes you thank her for doing it.

It seems clear that much of Snyder’s audience has wrapped up their whole identity in his films. Many of these fans seem to be people with a very specific idea of masculinity, and some level of insecurity about their own identity. Is it surprising, then, that if they’re going to watch a superhero movie, it needs to be a totally metal superhero movie where Superman wears black and silver instead of red and blue?

Obviously I’m not saying they’re all insecure or emotionally stunted, nor am I saying that they are all old enough to have lived through the “getting bullied for comics” phase of life. Rather, I’m offering this as an archetype that I think a significant number of Snyder’s superfans fit into. It helps to explain what is so appealing about his characters and they way they cannonball through life, crushing and humiliating those who oppose them.

How Zack Snyder (Accidentally) Became A Populist Hero

There is a perception — one that’s often wrong, but still pervasive — that studios only make movies worse, and that “director’s cuts” are always better than whatever compromise a filmmaker needs to make to get butts in seats. Snyder has become a mascot for this philosophy.

On a recent episode of the Emerald City Video podcast, Zach Roberts and I touched on this, talking about movies like Payback, with a director’s cut that’s absolutely dogshit.

Snyder’s “Ultimate Cut” of Watchmen was a big seller during the heyday of DVD and Blu-ray, addressing some of the critiques of the movie’s theatrical cut and offering something entirely unique to the home video audience. It had detractors, particularly since adding in the animated Tales of the Black Freighter element killed a lot of the movie’s pacing, but some insisted it was the definitive version of the film.

He also had unrated cuts of Dawn of the Dead and Sucker Punch released, both of which were negligibly different from the theatrical cuts. With no serious quality difference, fans seemed to just shrug and decide Snyder’s cut was better. Because why not?

His version of Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice was, as I alluded to above, a marked improvement over the theatrical cut. While its runtime was bloated, there were scenes included in Snyder’s cut that were inexplicably cut from the theatrical version, leaving plot holes and question marks for cinema audiences.

And then came Justice League. Ohh, Justice League.

There are a lot of different versions of exactly what happened, and some of what I believe to be true, I was told off the record. So here’s a pretty bare-bones version:

Snyder and the studio were at odds after Batman v Superman failed to make $1 billion. That mark, set by a number of then-recent Marvel releases, was seen as the expectation for a lot of big budget tentpoles…but certainly for the one that had Batman, Superman, and Wonder Woman in it.

Shortly after Snyder’s daughter died by suicide, he was either fired or quit Justice League. It’s my understanding that he tried to stay on and finish the movie, but ultimately quit when it became evident that the process was going to be overly stressful.

Joss Whedon stepped in to finish the movie. Whedon, who had just made The Avengers, was seen as “the enemy” by some fans who thought Marvel’s movies were too juvenile and silly. How could The Avengers guy possibly do Snyder’s Frank Miller-inspired epic justice?

Whedon did a poor job of reworking the film, churning out a version that nobody liked and which made much, much less money than Batman v Superman did.

Snyder’s fans immediately seized on the idea that the director’s assembly cut, which had been cut together shortly before he left the project, would be far superior to the theatrical cut.

Those same fans thought, rightly or not, that they were being denied Snyder’s cut by executives whose priority was not the best interests of the film or audience.

You can see how those last few points map neatly onto the long-standing mythology of The Director’s Cut. It isn’t unique to Snyder, but he has become the best-known example in recent memory of what can go wrong when the studio seizes too much creative control.

Shortly before he left the project, Snyder had a handful of reporters to the set of Justice League for a visit. There, he talked about ambitious plans for sequels and spinoffs which would never come to pass, while simultaneously revealing that the originally-planned Justice League Part Two was no longer guaranteed. Fans excited by the sound of his plans, as well as those just frustrated by studio meddling, took Snyder’s “side.”

All of this was happening alongside the rise of right-wing populism in America, much of which is linked to evangelical Christianity. That means people with a really specific, narrow vision of masculinity and a black-and-white sense of morality were out there daily, expressing how they felt slighted by the powers that be. The same narratives that led to the rise of right-wing populism map pretty cleanly onto the movement that grew to demand Warner Bros. #ReleaseTheSnyderCut.

Again, this is not to say that all of Snyder’s fans — even the vocal ones — are Trump supporters or right-wing extremists. But the same factors that led to the rise of Trump likely contributed significantly to Snyder’s elevation to folk hero.

One key element of modern day populism is a rejection of experts of all stripes. In the case of the Snyder fandom, that includes film critics, film scholars, and other learned types who use ten-cent words to pillory Snyder’s movies. The incorporation of populist philosophy into the Snyder base also explains how they became so conspiratorially-minded, often convinced that positive and negative reviews can be bought.

The through line here, and what makes so much of their behavior feel cult-like, is the confidence that they know more and better than anyone else. They’re positive that Warner Bros. and Joss Whedon fucked up the movie. They’re certain that bad reviews are a conspiracy. They’re sure Disney and Marvel are somehow behind it.

A Lot of People Who Don’t Like Snyder Are Also Assholes

It’s a lot harder to convince people that there’s no conspiracy, they aren’t being targeted, and everything is normal when they can plainly see that they are, in fact, being targeted. Hell, this whole article started with a subreddit that’s about mocking not Snyder or his movies, but his fans.

The interactions between those who love Snyder’s movies and those who hate them became insufferable pretty early on. I was told on multiple occasions that I was a bad person, or didn’t understand Superman, or both, because I enjoyed Man of Steel — a movie I admitted had flaws.

The long list of ways Snyder’s supporters have been irritating and destructive has been exhaustively documented, but it’s much rarer that his detractors end up under that same microscope. For people who are conspiratorially minded, that kind of one-sided attention feels like validation of their persecution fantasies.

And, yes: there are a lot of assholes on both sides. When Man of Steel debuted on Rotten Tomatoes with 100% positive reviews (for about four hours), the first person to give it a bad review got death threats and a mountain of abuse. Eventually, the ratings evened out in the 70s and eventually fell to the high 50s, but for the next few years, the narrative around the movie seemed to be that everybody hated it.

I saw for myself not only the way fans of the movie were mocked online, but the absolutely gleeful way critics and Snyder detractors celebrated the failure of Batman v Superman. A mediocre superhero movie somehow became the worst thing ever made in the history of ever, and the critics and reporters who cover the pop culture space were celebrating. The narrative that nobody could really like this movie was born early, reinforced often, and beaten into the movie’s fans. The result is that fans of the movie, and Snyder supporters more broadly, became battle-hardened by the mockery.

What happens when somebody allows way too much of their identity and self-esteem to be wrapped up in a thing, only for experts and the media to gleefully declare that it’s dumb, and they’re dumb for liking it? A huge number of them double and triple down. The populist streak that had started to infiltrate Snyder’s fandom kicked into high gear, rejecting expertise and lining up behind a fast-developing cult of personality around Snyder.

And of course, the movie itself provided a perfect, meme-able way to argue:

OWNED, amirite?